On January 13, 1971, Congress passed the Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Act, which prohibited the use of lead-based paints (“LBPs”) in residences constructed or renovated by the federal government or using federal assistance. Fifty years later, we are still seeing the health impact of LBPs and other leaded products. But why was lead used in the first place? In this blog, TRG explores the history and health effects of leaded products and shares how companies can use our services to address lead contamination.

Lead Based Paints continue to pose health risks. Image via openverse.org

A History of Leaded Products

Lead has been used by humans for millennia for a variety of purposes. It is malleable, , has a low melting point, and can be found across the globe. Until the 1970s lead-based glazes were commonly used to seal dishes and other ceramics, as it gave items a bright and smooth finish—a technique with origins in both ancient Rome and China. Lead jewelry was once commonplace, and even today can be found in vintage jewelry as it was used to make colors brighter and add desirable weight. The Romans used lead so extensively in their innovative system of water distribution and drainage that it became synonymous with the metal: plumbum (its Latin name, from which derive both the modern word “plumbing” and lead’s chemical symbol, Pb). Today, drinking water in many American communities is still provided via lead pipes. Lead has been used to make tools and toys, fuel additives and industrial equipment.

Lead-based paints (“LBPs”) became popular in the early 20th century because of their appearance and durability. Advertisements for LBPs touted the ability of these readily available paints to withstand weathering, being moisture-resistant and therefore less likely to be damaged by rain and humidity. LBPs were also lauded for their relatively short drying time, compared to other paints. Many buildings both public and private, including schools and government-provided housing, were coated with LBPs. So too were many other everyday items, including toys, baby cribs, and household decorations.

LBPs were popular due to their durability, however the resulting lead contamination has had a lasting impact. Advertisement via Duke University Library Outdoor Advertising Collection

Childhood LBP Exposure

The danger of LPBs comes from the paint degrading over time, resulting in dust and flakes that can be easily ingested. Inquisitive toddlers often teethe on the objects around them and were at risk of consuming lead from their toys and beds. Even children playing in the soil next to a house painted with LBP risked exposure to lead particles.

Children are especially vulnerable to lead poisoning, with the World Health Organization noting that small children are susceptible to absorb four to five times as much lead as an adult. Furthermore, lead tastes sweet, so children who instinctively put paint chips or other leaded substances in their mouths are less likely to spit the objects out. Childhood exposure to lead impacts developing brain function, can damage major organs, and can lead to behavioral issues later in life.

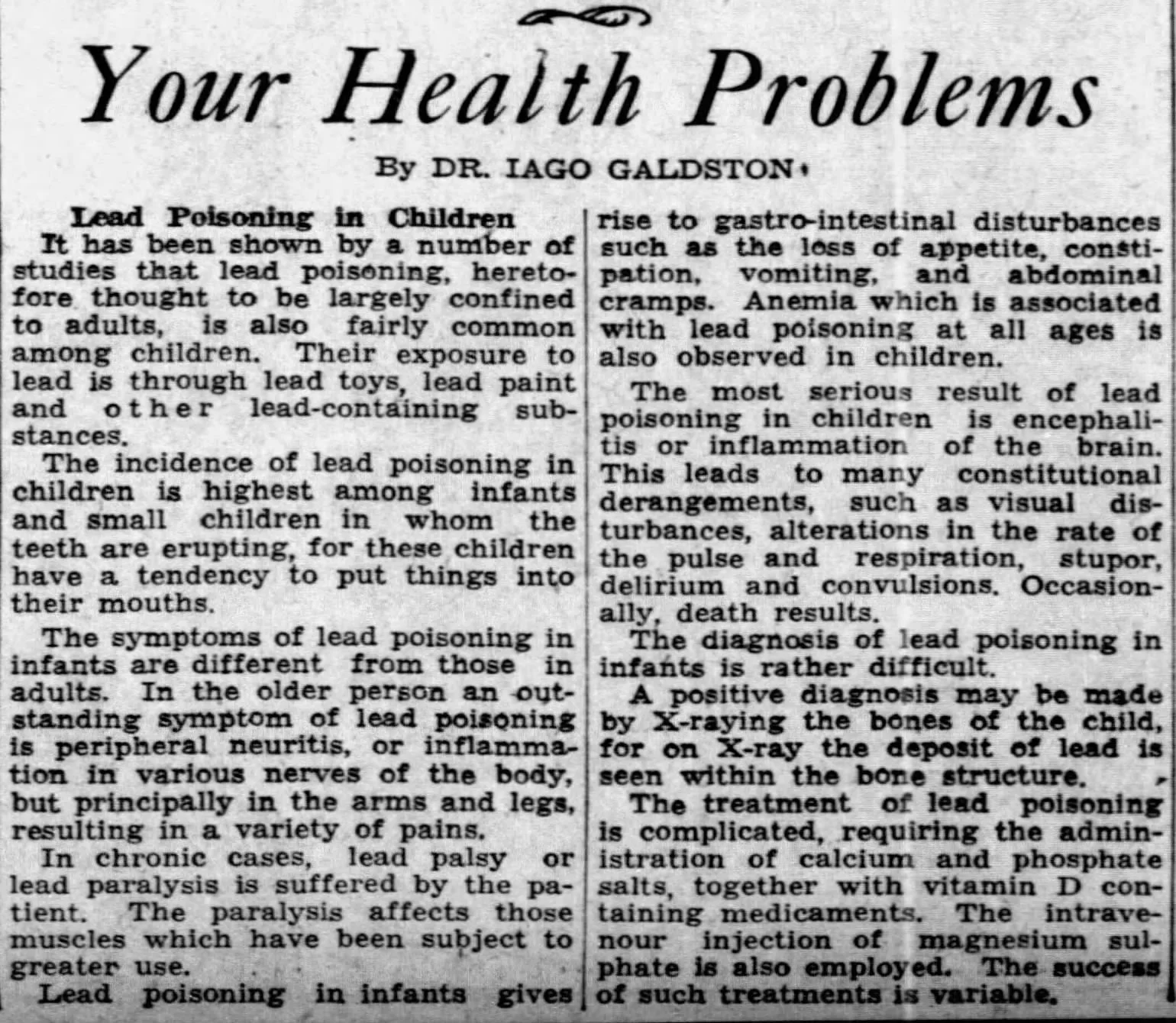

In this column, Dr. Iago Galdston warns parents about the dangers of childhood lead poisoning. Source: The Palladium-Item, Richmond, Indiana, February 5, 1934.

Reports of the dangers of childhood lead poisoning, were being published by the mid-1930s. For example, Dr. Iago Galdston’s widely syndicated column Your Health Problems (or in some newspapers, How’s Your Health?) included a piece on lead poisoning in children in 1934. The article noted that children’s “exposure to lead is through lead toys, lead paint and other lead-containing substances.” Still, LBPs continued to be widely used for the next forty years.

Continued research into childhood lead exposure, and continued public attention on the impact of lead exposure in general, led to widespread lead legislation during the 1970s. Following the 1971 Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Act, in 1973, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (“CPSC”) banned hazardous levels of lead in toys and other products intended for use by children. Further legislation aimed to address lead levels in air, water, and gasoline continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In 1991, the Center for Disease Control (“CDC”) created the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, to support state and local efforts to protect children from lead exposure. According to the CDC, the average blood lead levels in children ages 1-5 “have declined from 15 micrograms per deciliter…in the late 1970s to less than 1 [microgram per deciliter]” in the early 2010s.

Continuing Lead Issues

Despite the legislative and scientific advancements made over the last 50 years, lead exposure continues to be a problem. Studies show that many children are still exposed to lead, especially in low-income areas. As we shared this past fall, small planes using leaded fuel are “the dominant source of lead emissions in our air.”

Taylor Research Group’s team of experienced fact-finders have conducted extensive historical research related to lead pollution, including site and industrial plant histories as well as potentially responsible party (“PRP”) investigations. Our familiarity with the relevant federal, state, and local records, and our experience in helping clients build their environmental and toxic tort cases makes TRG an ideal partner when it comes to lead or other heavy metals-related litigation research.